Last week, one of the big stories in evangelical news concerned a fairly heated conversation that Asian American and Hong Kong evangelicals have been having about Rick Warren’s Red Guard Facebook photo. Unintentionally, this blog participated in bringing this issue to a wider public. The story was also picked up by the news media, keeping the issue public even while Warren has deleted the photo, issued a response on one of the most visible bloggers’ blog, and apologized conditionally on his public Facebook wall.

The question that some have asked us is: now that there has been an apology, why have we left our blog posts up?

Our answer has been that it is important to maintain the integrity of the public record. But this is not enough for some who object to what we are doing. For our objectors, that sort of answer is a secular one, that to be public is to be ‘worldly’ (as opposed to being ‘churchly’) and that to be on the record is to fail to love Warren; after all, doesn’t St. Paul tell us that ‘love keeps no record of wrongs’ (1 Cor. 13.5 NIV)? Accordingly, their charge against us is that we are not being Christian. Here are some of the more popular ones that I hear:

- Rick Warren has done a lot of good for the kingdom. By leaving the posts up, you are damaging his ministry by tarnishing his reputation. He took down his post and apologized. Shouldn’t you take down your post before you wreck his ministry?

- I’m not offended. I’m sorry if you were. Even so, Rick Warren has apologized because you are part of the group of highly sensitive people that was offended. Shouldn’t you stop focusing on yourself and your pride and refocus on Jesus?

- If you keep the post up, all that the outside, non-Christian world will see is Christians bickering. That is a poor witness, and you are making it worse. How will the world understand us by our love? How will the church be able to reach the world for Jesus when all we do is fight?

- You need to reconcile with Rick Warren. Reconciliation can only happen when you forgive him. Forgiveness means that you have to wipe the slate clean, just like God does with our sin.

- I am not perfect. Rick Warren is not perfect. You are not perfect. Who are you to judge Rick Warren? You would never want to be judged like you judge him. That’s why Jesus says not to judge.

What our objectors want is a theological answer. This is it.

The short answer is: we have left the posts up because we are Christians, and our theology is orthodox.

In the late modern world, Christians who practice orthodox theologies have often felt themselves besieged by a world that no longer believes that truth is objective. Objective truth means that what is true exists outside of one’s subjective experience and remains true despite attempts to subvert it in favour of alternate ideologies, especially powerful political interests. Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI called the modern loss of this sensibility the ‘dictatorship of relativism,’ the notion that in a world where truth is merely reduced to one’s individual perspective, then the stories that are told in that society will be co-opted by powerful individuals and institutions with the ability to stamp their version of truth onto the world and call that ‘the truth.’ For those of our critics who are uncomfortable with a Catholic citation, note well that this has also been a common evangelical complaint, one that is often heard in apologetics classes written by Josh McDowell, church-state relations seminars using the work of Charles Colson and Fr. Richard John Neuhaus (oops, I did it again: another Catholic!), taught especially by the neo-Reformed tribe to defend their allegiance to the Gospel’s propositional truths, and generally complained about by culture warriors opposing abortion, same-sex marriage, euthanasia, ideologized public education, and the encroachment of the state onto matters of religious freedom. Although the writers of this particular blog have often felt that the theological divisions between Catholics and evangelicals are becoming increasingly artificial, we grant for the readers of this particular post that they are still separate ecclesial entities. And yet they agree on one core contention: that truth is objective.

Without stating our position on the above culture war issues, we affirm as orthodox Christians that we believe in the objectivity of truth.

From Kathy Khang’s reflection on Warren’s public apology, we know that Khang believes strongly in the objectivity of truth. After all, she meant what she said when she wrote that she ’emailed Rick Warren and there is no “if”.’ She is saying that her being offended by the image is not merely a subjective feeling. Unlike Professor Sam Tsang, neither Khang nor her Korean American family had any connection with the Cultural Revolution. So too, Tsang, who spent the last weekend preaching at a retreat hosted by a pan-Asian American church whose origins are Japanese American, told me (and I quote with his permission), ‘I heard from my Japanese brothers and sisters when I preached this weekend. loud and clear, We’re with you!‘ These non-Chinese Asian Americans had no subjective reason to be offended. But they were. This is because the offence was objective.

What was objective about the offence was its complicity with a process of orientalization. Orientalization is the process by which ‘orientals’ are made. ‘Orientals’ are a collective image of Asians and Asian Americans as collectively different from persons from the West, a set of images that regards them (as Edward Said famously put it) as static, backward, conservative, kinship-oriented, and immutably exotic. As theologian J. Kameron Carter describes it, orientalizing ideologies have been responsible for the problem of race in modern theology, including (as he fascinatingly makes the argument) the enslavement and subsequent subjectification of African Americans in American life. This is because modern orientalizing ideologies conveniently located those of different coloured skins from ‘white’ Europeans as inferiorly different, which meant that they could be colonized, traded as objects, and subordinated into inferior positions. Indeed, despite recent conflicts in the last twenty years between Asian Americans and African Americans, scholars and activists of race have long recognized that their common experience of racialization should have made it easy to develop solidarities between the two groups. That solidarity is hard to come by is a subject for another discussion.

The point, though is that orientalization was, is, and continues to be a process of continual offence, regardless of how it is received subjectively. This puts to rest the notion that the offensive Facebook photo could not have been offensive because some Asians and Asian Americans–perhaps even a large swath of them–were not subjectively offended by the post.

The point, though is that orientalization was, is, and continues to be a process of continual offence, regardless of how it is received subjectively. This puts to rest the notion that the offensive Facebook photo could not have been offensive because some Asians and Asian Americans–perhaps even a large swath of them–were not subjectively offended by the post.

No, we believe in the objectivity of truth.

Accordingly, we observe that the initial Facebook photo post was offensive because it objectively objectified Asians and Asian Americans. This was an offence because it treated Asians and Asian Americans as objects, not as persons. There is a difference. A person is someone with whom one shares communion. A person has agency to converse, has the ability to either agree or to disagree, is capable of talking back and thinking and walking together with people with whom he or she can relate in the myriad of ways that persons can. An object has no agency. An object cannot be communed with. An object has no agency to converse, has no ability to either agree or disagree, is incapable of talking back and thinking and relating. Orientalization is the process of reducing Asians and Asian Americans from persons to objects.

Whatever one feels about being treated as an object and not as a person, and whatever one intends in even the accidental, ignorant proliferation of images and discourses that perpetuate this objectification, is irrelevant here. The objective truth that treating people like objects and not as persons is a violation of any person’s objective dignity as an imagebearer of God himself. In short, the objective truth that is declared by the Christian faith is that all humans are made in the image and likeness of God and thus have dignity as persons. To objectify another human–that is, to deny a human being his or her personhood and agency by reducing him or her to an object–is to offend against this objective truth. This objectification need not be subjectively intended; in other words, Warren did not need to have any malicious intent in posting the photo of the Red Guard. Neither does this objectification need to be subjectively received as such; the result was that, of course, some Asians and Asian Americans were fine with Warren’s humour. Instead, the process of objectification describes an observable, objective effect: objectively speaking, does the photo with its caption treat Asians and Asian Americans as persons with whom to be communed or convenient objects to be used as the butt of jokes? Was this the image of a person made in the image and likeness of God, or was it the image of an object that could be conveniently used to make a funny point?

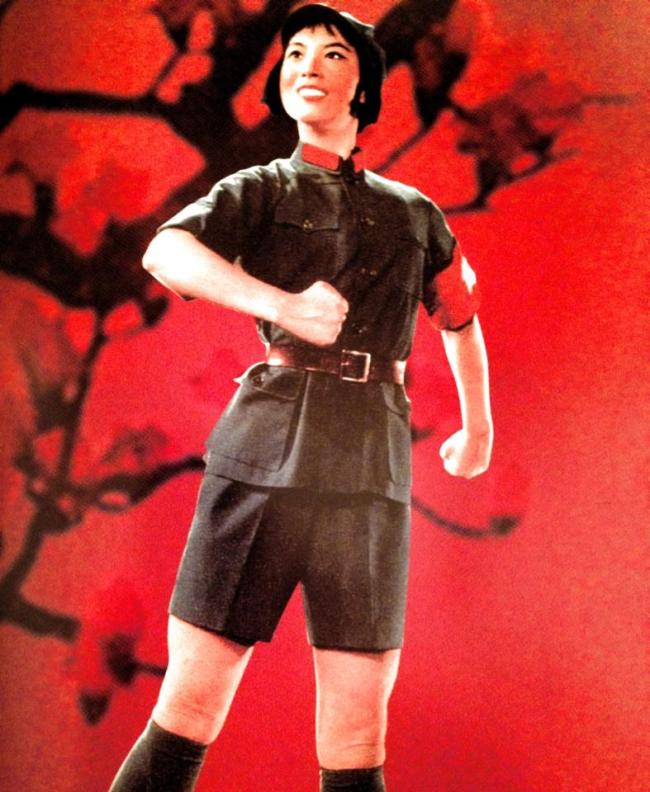

Warren’s initial response suggests that the latter is true. That Warren then declared ‘it’s a joke!’ indicates, regardless of whether he was thinking this or not, that it was inconvenient for him that the ‘orientals’–the objects–were talking back as persons. He did not need to think this. Again, we are looking not at his subjective experience, but the objective, observable situation. His message was this: ‘orientals’ should not talk back; ‘orientals’ should be content to be the objects that they are; ‘orientals’ should not be listened to as persons. Those offended were framed as ‘orientals,’ suggesting that the ‘oriental’ image displayed on the photo should not be read as a Red Guard with whom communion can be shared. She was an object–an ‘oriental’ object–whose sole function was to make a funny point.

Our contention is that attempts are now being made to twist this objective truth.  Warren’s initial defence achieved an interesting twist on the relationship between persons and objects. Warren then explained that the ‘disciples’ would have understood his humour while the ‘self-righteous’ would not have comprehended it. Perhaps unintentionally at a subjective level and likely without malicious intent, Warren was saying that Asians and Asian Americans are to be regarded by the disciples of Jesus Christ–the church–as the objects of jokes and those who would dispute this use of humour are the ones who are self-righteous, the ones that would in turn crucify the Lord of glory.

Warren’s initial defence achieved an interesting twist on the relationship between persons and objects. Warren then explained that the ‘disciples’ would have understood his humour while the ‘self-righteous’ would not have comprehended it. Perhaps unintentionally at a subjective level and likely without malicious intent, Warren was saying that Asians and Asian Americans are to be regarded by the disciples of Jesus Christ–the church–as the objects of jokes and those who would dispute this use of humour are the ones who are self-righteous, the ones that would in turn crucify the Lord of glory.

Understanding this theological twist is key to comprehending why it is that those who are arguing for the objective, dignified personhood of Asians and Asian Americans have been suddenly framed as the enemies of Christ. Regardless of Warren’s interior motives, the theological effect that has been achieved is that those who are defending the personhood of Asians and Asian Americans are framed theologically as the offensive aggressors, the ones who are now crucifying Warren for his use of humour. In so doing–again, regardless of personal motive–Christian theology has been rewritten. Defenders of personal dignity are framed as aggressors. Those whose actions (regardless of intent) result in the objectification of persons are described as Christ-like martyrs. The irony could not be more striking.

This theological twist is magnified by the attempts to erase and rewrite the public record. To advocate this is (according to our objectors) to advocate forgiveness and grace. From the deletion of comments on Warren’s Facebook wall calling for a public acknowledgement of the objectiveness of orientalizing offence to the vitriolic objections of our objectors pleading for us to delete our posts, attempts are being made to ‘wipe the slate clean.’ It is in this context that Warren’s response on Professor Sam Tsang’s blog and his conditional apology on his public Facebook wall should be read: they are attempts to wipe the slate clean without acknowledging the objective truth that orientalization is an objective offence against the dignity of human persons. As theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer put it in Discipleship, this is ‘the preaching of forgiveness without requiring repentance, baptism without church discipline, communion without confession, absolution without personal confession.’

This theological twist is magnified by the attempts to erase and rewrite the public record. To advocate this is (according to our objectors) to advocate forgiveness and grace. From the deletion of comments on Warren’s Facebook wall calling for a public acknowledgement of the objectiveness of orientalizing offence to the vitriolic objections of our objectors pleading for us to delete our posts, attempts are being made to ‘wipe the slate clean.’ It is in this context that Warren’s response on Professor Sam Tsang’s blog and his conditional apology on his public Facebook wall should be read: they are attempts to wipe the slate clean without acknowledging the objective truth that orientalization is an objective offence against the dignity of human persons. As theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer put it in Discipleship, this is ‘the preaching of forgiveness without requiring repentance, baptism without church discipline, communion without confession, absolution without personal confession.’

Although Tsang acknowledged Warren’s first response as an apology, it is better described as a responding comment. In this comment, Warren stated that the photo was ‘instantly removed.’ Whatever one’s subjective interpretation of the passing of two days might be, this is not objectively true. It is objectively true that Warren’s ‘instant’ response was to suggest that those who did not find his joke funny were ‘self-righteous’ whereas those who were giggling were like the ‘disciples.’ Moreover, Warren tells Tsang to contact him ‘directly.’ A better word choice here is ‘privately.’ Attempting to hide the objective truth that this incident began publicly, the response here wipes that slate clean and puts the blame on Tsang for not approaching him through a private channel. Khang then attempted to do exactly as Warren said: she sent an email to Warren ‘directly.’ It was met with a generic, indirect response. This suggests that ‘private’ is indeed a better word.

As Khang eloquently states, the effect of this maneuver (whatever its intent) was that she was ‘silenced.’ Indeed, that initial response generated three tactics by which the objectively existing public record has been fudged. In particular, the tactic that has been used is to turn the objective offence of orientalization into a subjective experience. First, Warren himself touted his credentials as someone who initially wanted to plant a church in Japan and then the doors were closed. Second, immediately after this comment, L2 Foundation’s D.J. Chuang (himself a member of Saddleback Church) then commented on each of the bloggers’ walls (including this one) reiterating, ‘That post was removed immediately and personally by Pastor Rick as soon when he learned how the photo was offensive.’ Third, Asians and Asian Americans themselves–likely without any prompting from Warren or Saddleback–began to accuse the bloggers of failing to represent the universal experience of Asians and Asian Americans, for many proclaimed themselves that they did not feel offended, that is, that they did not subjectively process the objective offence of orientalization as a subjective offence.

Note: though these photos are from the public conditional apology and have a later date than those described in these present paragraphs, they illustrate the types of comments that have occurred. As Khang notes, earlier comments that would have been available were deleted along with the original photo.

In so doing, the record–the objectively existing public conversation that exists outside of Saddleback’s private control–has been fudged. Warren declares his solidarity with all Asians by touting his missionary credentials. An Asian American himself comes to Warren’s defence on each of the blogs. Asians and Asian Americans unhappy with the bloggers declare that they are not subjectively offended. The problem is that none of these responses got at the heart of the objective offence of orientalization. To be missionary minded toward Asians does not erase an act of orientalization. To have a prominent Asian American evangelical come to one’s defence does not lessen the objectivity of this offence. To have Asians and Asian Americans declare that they did not subjectively receive the offence as an offence does not mean that it was not an offence. Orientalization is an objective offence. But this process of damage control has subverted the perception of orientalization as objective. It is now subjective simply because people now say it is.

And the result is that those who protest the objective offence of orientalization are silenced. Khang tells us that she ‘felt silenced.’ No, Kathy, you do not only feel silenced. You were objectively silenced.

And the result is that those who protest the objective offence of orientalization are silenced. Khang tells us that she ‘felt silenced.’ No, Kathy, you do not only feel silenced. You were objectively silenced.

Following the publication of a Religion News Service article, though, Warren then issued a public conditional apology on his Facebook wall. The apology was conditioned by an if: if we were offended, then the apology applies to us. What this amounts to, however, is the further subjectification of an objective offence. It suggests that the offensiveness of orientalizing objectification is conditioned by how it is subjectively received. It means that if someone is not offended, then an image that strips human persons of dignity by turning them into objects is not offensive for some people. Kathy Khang is right to object to the conditionality here: ‘Words matter,’ she says. Or to quote her in full:

Following the publication of a Religion News Service article, though, Warren then issued a public conditional apology on his Facebook wall. The apology was conditioned by an if: if we were offended, then the apology applies to us. What this amounts to, however, is the further subjectification of an objective offence. It suggests that the offensiveness of orientalizing objectification is conditioned by how it is subjectively received. It means that if someone is not offended, then an image that strips human persons of dignity by turning them into objects is not offensive for some people. Kathy Khang is right to object to the conditionality here: ‘Words matter,’ she says. Or to quote her in full:

There is no “if.” I am hurt, upset, offended, and distressed, not just because “an” image was posted, but that Warren posted the image of a Red Guard soldier as a joke, because people pointed out the disconcerting nature of posting such an image — and then Warren told us to get over it, alluded to how the self-righteous didn’t get Jesus’ jokes but Jesus’ disciples did, and then erased any proof of his public missteps and his followers’ mean-spirited comments that appeared to go unmoderated.

I am hurt, upset, offended, and distressed when fellow Christians are quick to use Matthew 18 publicly to admonish me (and others) to take this issue up privately without recognizing the irony of their actions, when fellow Christians accuse me of playing the race card without trying to understand the race card they can pretend doesn’t exist but still benefit from, when fellow Christians accuse me of having nothing better to do than attack a man of God who has done great things for the Kingdom.

Khang is objecting to the process of objectification being framed as just another subjective experience. It is not subjective. It is an objective offence. There is therefore no ‘if.’

To resist this silencing, our objectors say, is to fail to forgive. In so doing, we are accused of being the ‘self-righteous’ who are crucifying Warren, tarnishing his reputation, and bringing shame to the church by continuing our bickering. To cease to be objects of orientalization, to assert ourselves with the personal dignity that is objectively ours by virtue of our creation, is to sin, according to our objectors. Our actions are described as prideful; our assertions are characterized as divisive; our call for Asian and Asian American agency is judged as judgmental. Our objectors seem, in short, to be able to wield the power to define what is good and what is evil. On the other hand, we as orthodox Christians committed to the objective truth of the person are not only incapable of wielding such strange sovereignty; we refuse to do so because we understand this seizure of truth to be eating from the very tree of the knowledge of good and evil for which our ancestors were cast out of paradise. And yet for not capitulating to our objectors’ theological rationality, we are labeled as the ones who should be cast out of the church. Indeed, this has already happened to at least one of us this week: Professor Sam Tsang has been asked repeatedly by our objectors whether or not he is a ‘born again Christian.’ Our objectors are powerful. They have, it seems, the power even to excommunicate.

To resist this silencing, our objectors say, is to fail to forgive. In so doing, we are accused of being the ‘self-righteous’ who are crucifying Warren, tarnishing his reputation, and bringing shame to the church by continuing our bickering. To cease to be objects of orientalization, to assert ourselves with the personal dignity that is objectively ours by virtue of our creation, is to sin, according to our objectors. Our actions are described as prideful; our assertions are characterized as divisive; our call for Asian and Asian American agency is judged as judgmental. Our objectors seem, in short, to be able to wield the power to define what is good and what is evil. On the other hand, we as orthodox Christians committed to the objective truth of the person are not only incapable of wielding such strange sovereignty; we refuse to do so because we understand this seizure of truth to be eating from the very tree of the knowledge of good and evil for which our ancestors were cast out of paradise. And yet for not capitulating to our objectors’ theological rationality, we are labeled as the ones who should be cast out of the church. Indeed, this has already happened to at least one of us this week: Professor Sam Tsang has been asked repeatedly by our objectors whether or not he is a ‘born again Christian.’ Our objectors are powerful. They have, it seems, the power even to excommunicate.

In other words, the situation in which we find ourselves has degenerated precisely to the point where it could be called a ‘dictatorship of relativism,’ a scenario in which what is true is dictated by might and not by an objectively existing truth that cannot be bent by the powerful to their own interests. By calling this present situation a dictatorship of relativism, we in no way imply that Rick Warren is a dictator. We are saying instead that our communion with our brother, Rick Warren, has been co-opted by a relativist ideology. This is a sad state of affairs because relativist notions of truth hold no possibility for objective forgiveness and reconciliation.

In other words, the situation in which we find ourselves has degenerated precisely to the point where it could be called a ‘dictatorship of relativism,’ a scenario in which what is true is dictated by might and not by an objectively existing truth that cannot be bent by the powerful to their own interests. By calling this present situation a dictatorship of relativism, we in no way imply that Rick Warren is a dictator. We are saying instead that our communion with our brother, Rick Warren, has been co-opted by a relativist ideology. This is a sad state of affairs because relativist notions of truth hold no possibility for objective forgiveness and reconciliation.

They preclude it.

The objective of this practice of relativism is to return this present situation to a certain status quo, a situation in which Asians and Asian Americans are not in active conversation with Warren, the state of affairs that existed prior to Monday morning. In this status quo, however, Asians and Asian Americans will not have been reconciled to Warren as persons. We will still be objects, ‘orientals’ who cannot and should not speak back. But this ‘peace’–this constructed harmony in which there will be no more visible contestation–does not return us to the objective truth declared by the Christian faith that all humans are created as persons in the image and likeness of God. It leaves us with a situation in which the objectified are still objects and the persons are not reconciled.

An orthodox Christian theology bears witness against this dictatorship of relativism. An orthodox Christian theology insists on the objectivity of truth and insists further that that objective truth is to be found in the person of Jesus Christ. It is from Jesus, not from our objectors, that the cross is truly understood, that the forgiveness of sins is achieved, and that the communion of persons is realized and restored. It is because truth is objective–it exists outside of what anyone says it is–and it is objectively found in Jesus.

‘The light shines in the darkness,’ the Gospel according to St. John (1.5) begins, ‘and the darkness has not overcome it.’ The true light of Jesus Christ’s objective truth subjects this dictatorship of relativism to a crisis. While the discourse has fudged the objectivity of objectification, we recognize in Jesus, the very image and icon of God, that redemption means the restoration of all human dignity from processes of objectification. As St. Irenaeus puts it in his interpretation of the prophet Ezekiel’s vision of one like a son of man coming as the glory of God, ‘The glory of God is a human being fully alive’ (Adversus Haeresus IV.20.7). Confronted with the person of Jesus Christ, the subjectifying logic of orientalization crumbles. ‘The time is fulfilled,’ the Lord declares (Mark 1.15), ‘and the kingdom of God has come near; repent and believe in the Gospel.’

From Jesus, we understand that the cross was the last resistance of those who wish to pronounce for themselves what is good and what is evil. By challenging the logic of objectification, Jesus challenged the reduction of persons into objects by the powerful to preserve their own interests. For doing this, Jesus was betrayed, beaten, flogged, and crucified. Jesus was silenced. But in that process, that which was hidden from the foundations of the world was revealed. The challenge to objectification provoked the murder of the Lamb of God. Objectification is revealed as a process of violence, for its perpetrators and defenders must silence, must fudge, and must kill those who object to the reduction of persons into objects. But by killing Jesus, the power of such dark practices is broken, for the illegitimacy of their actions is revealed. As St. Paul says of the cross, ‘He disarmed the rulers and authorities and made a public example of them, triumphing over them in it’ (Cor. 1.15). The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it.

From Jesus, we then understand forgiveness to be the love that he shows us in his resurrection as an embodied person, seeking not vengeance but communion with those who abandoned him and crucified him. Having rendered the power of sin and death powerless by exposing its illegitimate core, Jesus does not return in vengeance. He rises from the dead to love the very people who abandoned him and killed him. He calls Mary by name. He breathes the Holy Spirit on the followers who abandoned him at the cross. He invites St. Thomas to put his finger in his nail marks and his hands in his side. He reinstates Peter with the words, ‘Feed my sheep.’ He sends the Holy Spirit on the church at Pentecost, from where the people that St. Peter accuses of crucifying Jesus grow into the first Jerusalem church. This is forgiveness: the maintenance of the cross on the public record as a moment when the things hidden from the foundations of the world were revealed and exposed, and yet the unexpected embrace of the crucified one toward those who did not know that they had killed the Son of God. In his resurrection, Jesus forgives, and the cross is transfigured–it is not erased–into an instrument of love. The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it.

From Jesus, then, we understand the church to be a communion of persons, the very Body of Christ that lives out the objective truth at the core of our common existence: that we are made for communion with God and with our brothers and sisters. If orientalization has happened in this Body, it must be confessed, exposed, and forgiven. That it has no place in the church does not mean that it does not happen. When it happens, it must be revealed and not fudged; it must be judged and not excused; it must be confessed and not covered with fig leaves. As St. Peter writes in his first letter (4.17), ‘The time has come for judgment to begin with the household of God.’ The result, as St. Peter emphasizes in his entire letter, is that the church will perfect its communion in visible suffering, with its members clothed with humility. Indeed, the truth that would be manifested in the love that is shown would finally ‘cover over a multitude of sins’ (4.8). The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it.

And thus, if our critics have only the view that we must participate in their revision of Christian theology, then we must refuse for the sake of our participation in the objective truth manifested in Jesus Christ and handed down by his apostles. As St. John proclaims in his first letter (1.5, 7), God is light, and in him is no darkness at all. We must then walk in the light as he is in the light.

This, then, is what forgiveness entails. It is to call Rick Warren into fellowship with his Asian and Asian American brothers and sisters as persons, not as objects. This manifestation of communion must not be hidden from the world; it must be manifested in the full, visible unity between himself and those whom he mistakenly objectified. Warren must thus acknowledge that he, though likely without malicious intent, committed the objective offence of orientalization. He, as well as his followers, must commit themselves to a fuller communion with their Asian and Asian American brothers and sisters. In particular, he might himself accept the invitation to a public conversation about the lingering offence of orientalization in the church, seeking to discern with us all how we might live in the power of the Holy Spirit as ‘the holy catholic church, the communion of saints.’ That catholicity would be the sign that the kingdom of God is among us, that Jesus is present, and that the light shines in the darkness and the darkness has not overcome it.